It’s market day in my French town. And that makes the day special, even if it is a weekly occurrence.

While somewhat similar to farmers’ markets found in many US and Canadian towns, the regular street markets in French towns and Paris arrondissements (administrative districts) are more like public services provided and supervised by local town councils for the benefit of a town’s or district’s residents. They are integral to local social life, and necessary for many who do not have cars (whether by choice, or not). Markets are also perfect for single folk and the elderly who might want to buy only one or two carrots, one or two apples, a slice of cheese, an onion, and a single steak hache (fresh ground-beef patty)–small portions that are difficult to find in the grocery stores.

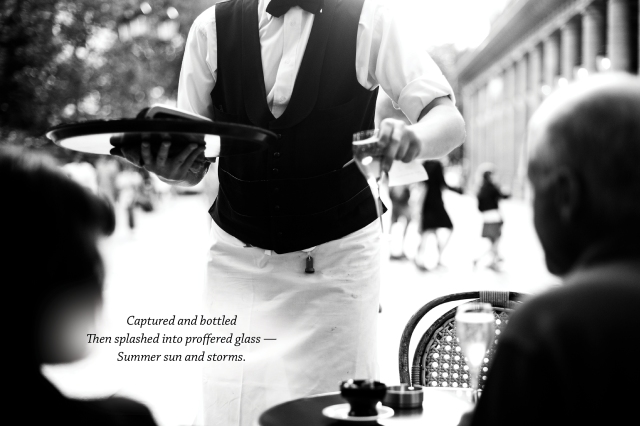

In my town, about 20 minutes west of Paris, the market days are Friday and Sunday. The Friday market is quiet and business-like. The Sunday market is boisterous and sociable, with the sidewalk cafes over-filled in good weather and lots of neighbors chatting as they stand patiently in line for fresh fish and vegetables, oysters, small-producer cheeses, roast chicken, Greek and Middle-Eastern delicacies, seasonal fruits, bunches of herbs, shoes and socks, bed and table linens, house-ware gadgets, bouquets of flowers, and more. Conviviality reigns and everyone fills their baskets and totes with lunch and dinner provisions.

Strollers, foot-powered scooters, wheelchairs, and dogs on leashes are all welcome along the town’s main street, where the collapse-and-store market stalls go up and down twice per week. No one is in a hurry. There is a surge to the crowd after mass ends at the Catholic church around the corner. At 1:00 pm, the vendors repack their vans with the unsold goods, and a few “gleaners” pick bruised fruit from the refuse piles. The town cleaning crew arrives to take down and store the rather ingenious market stall frames and roofs, then removes the trash and sweeps and washes the sidewalks where the bustling market stood just an hour earlier. The hosing prevents anything from rotting and smelling on the streets. By 4:00 pm you can walk down the street and not realize it had been market day at all–rarely even detecting the tiniest telltale odor at the spot where the fishmonger had stood.

We walk to market almost every week, whether or not we need food or intend to buy anything–just for the pleasure of it and the exercise. I miss the days when the kids were at home and we all walked together; now it’s just me and the hubby on our strolls. It’s one of my favorite aspects of life in France, and one that our sons remember with fondness, too. And, the haiku to mark the day:

cold Sunday morning–

market baskets all swinging

to ringing church bells

(P.S. There are websites that list the markets in every region of the country, giving their addresses and hours, and specialties, if any. Here’s a good one for Paris: http://marche.equipement.paris.fr/tousleshoraires )