All Come Together in Richard Wright!

When I started writing haiku seriously about two and a half years ago, I searched Amazon.com for haiku books to help me learn. My query brought up numerous English translations of Japanese haiku written by the four renowned old masters: Basho, Buson, Issa and Shiki. Then there were the how-to-haiku handbooks and modern collections and anthologies by members of various haiku societies. There were also over a dozen children’s books using the “traditional” haiku form to tell a tale or teach about the seasons.

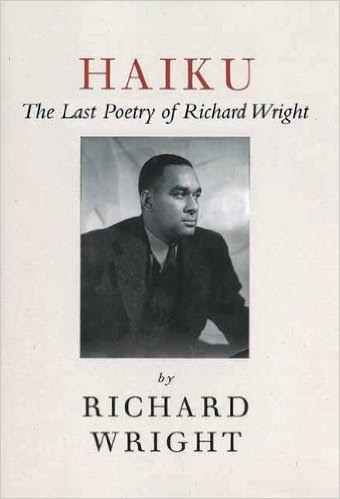

Then, there was a big surprise! Richard Wright (1908-1960), the author of Native Son (1940) and Black Boy (1945), Uncle Tom’s Children (1938) and Twelve Million Black Voices (1941), among many other works, had a large collection of haiku published posthumously in 1998. The surprise got even better—Mr. Wright had written all of them when he lived in France! I ordered a copy immediately. (See HAIKU: The Last Poems of an American Icon, by Richard Wright; Arcade Publishing, New York, c1998.)

I was encouraged by his prolific haiku outpouring. If such an esteemed literary figure, who wrote often about the African-American experience in the Deep South before the Civil Rights Movement, could suddenly embrace haiku and relish its elevation of the ordinary to the sublime—then haiku was a poetry genre worthy of my effort, too!

Healing Haiku

In the book’s introduction, written by his daughter, Julia Wright, we learn that haiku writing may have been a tonic, a respite, and a joy to this gifted writer whose health was declining, and who was grieving the loss of several people dear to him: his beloved mother, Ella; his friend and favorite editor, Ed Aswell; and his good friend Richard Padmore. Other unsettling events were unfolding in the last years of his life, too, including being embroiled in nasty Cold War politics stemming from his earlier connections with various Communist groups.

In the last 18 months of his life, unable to write longer works due to his failing health, Richard Wright wrote more than 4000 haiku and left his personal selection of 817 of them in a manuscript for his editor. His daughter writes in her introduction, “But writing these poems kept him spiritually afloat.” The American writer, who had moved to Paris, France, in 1946, in self-exile, died there in 1960, at age 52. He’s buried in Père Lachaise cemetery.

Almost all of his haiku are in the standard form taught at that time—in three lines of 5, then 7, then 5 syllables, with a seasonal reference. I gobbled them up, recognizing vintage French country-scapes in poem after poem. There were thunderstorms, blossoming fruit trees, cats, rats, dogs, snowflakes, horses, cows, crows and sunshine. There are another 3200 unpublished haiku hiding in a Yale library that I hope will see the light of day someday, too. In illness, being mindful of the natural beauty around him, Mr. Wright writes of wonder.

I read one review that suggested this haiku collection would have been more celebrated and appreciated if it had been published in 1960, soon after Mr. Wright’s death, when “5-7-5 haiku” were the accepted, unquestioned norm. But, thirty-eight years later, in 1998, when it was finally published, the accepted form of English-language haiku had changed.

Due to the great structural differences between the Japanese and English languages, including how to count “sounds” or syllables in their words, serious haiku poets learned that, more often than not, a17-syllable English-language haiku was much longer than a Japanese-language haiku with 17 “sounds,” a few of which even act as voiced punctuation. New standards for haiku writing in English evolved, so that by 1998, many of Wright’s haiku seemed a bit old-fashioned and long-winded to writers of more “modern” haiku.

Worth Your Time to Read

Oh, but there are gems here! And there’s evidence that Mr. Wright knew when just enough was said to make a perfect haiku—without counting syllables. He was a great wordsmith, after all. Here are a few of my favorites:

——————————————————-

Just enough of rain

To bring the smell of silk

From umbrellas.

———————————————

Yet another dawn

Upon yellowing leaves

And my sleepless eyes.

——————————————

Winter rain at night

Sweetening the taste of bread

And spicing the soup.

———————————————————

Last summer, my husband and I took a little “field trip” out to the tiny farming village of Ailly, in Normandy, where Mr. Wright had owned a country retreat. Many of his haiku were so obviously written there. Then we wandered around the serene “Le Moulin d’Andé” compound, once a cozy writers’ colony where Wright spent time with friends and fellow writers.

I stood at the edge of the mill pond and looked out over the water. I paid my homage by imagining him here with his friends, in the prime of life, with his family, relaxed and appreciated and free. The mill pond was teeming with life: little fish and frogs, sunning turtles, ducks and singing birds, and dragonflies, bright blue ones. And, of course, I wrote a haiku.

—————————————–

He stood here once …

Watching other dragonflies

On other lily pads.

—————————————-

I recommend HAIKU: The Last Poems of an American Icon, by Richard Wright; Arcade Publishing, New York, c1998.

The old writers’ colony at “Le Moulin d’Andé” in Normandy, as it looks today, with its mill pond.

Hello !

I am Ellen Wright-Hervé , Richard Wright was my grandfather, unfortunately he died 4 years before my birth. But his Haïkus have always touched me very profoundly, a form of identification I think!

I am so grateful for this celebration of his poetry , which he developed in his last years before his life ended unfairly early.

Ellen Wright-Hervé

LikeLike